Weekly, even daily, news media feature stories on the current opioid addiction crisis. At present, deaths from overdose of heroin, fentanyl, and similar drugs outnumber deaths from either gun injuries or auto accidents.

Often the stories read something like this fictitious example:

‘Alice’ was a single mother, working at a restaurant to support her two small children. When she hurt her back lifting crates of beer, her doctor gave her a prescription for 100 tablets of oxycodone. The medicine relieved the pain, but when the pills were all taken, she still had some pain, and also began suffering the symptoms of withdrawal. Weak from nausea and diarrhea, she was able to obtain some oxycodone pills at an outrageous price. An acquaintance told her that heroin was much less expensive and would keep her pain and withdrawal at bay. With time, she needed higher doses of the heroin to keep feeling decent, and eventually her life was consumed by her heroin habit. Her family spent all their savings on drug treatment programs, none of which worked for long. Unfortunately, her final heroin injection contained the very potent contaminant fentanyl, and she died of an overdose.

Heroin Addiction Today

Today about 75% of people with an addiction to heroin started taking opioid drugs as prescription medicines, according to Dr. R. Corey Waller of Health Management Associates, and many others. That statistic provides compelling evidence that the addiction story of the present is more complicated than weak will or unrestrained pleasure seeking. Most clinical and basic researchers are agreed that addiction is a chronic disease of the brain and should be treated on a physiological basis.

How do opioids work in the brain?

The Pleasure Pathway

Neuroscientists have known how addictive drugs like heroin work in the brain for several decades.

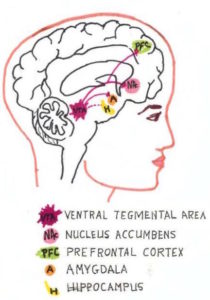

The normal brain has a checks and balance system for feelings of well-being. When nothing special is happening, a trickle of the neurotransmitting molecule dopamine is released by neurons in a certain area of the midbrain called the ventral tegmental area. Dopamine is the main neurotransmitter responsible for feelings of well-being and positive motivation.

Pleasurable activities such as sex, eating a good meal, or laughing at a joke cause the pituitary gland to secrete a class of small peptide hormones known as endorphins. Endorphins can bind to specific receptor proteins on neurons in the ventral segmental area of the brain. When endorphins bind to their receptors, a chain of biochemical events begins that result in at least doubling the amount of dopamine released. When the dopamine binds to its target neurons in the nucleus accumbens, these neurons spread the message that something good is happening.

Endorphins are also produced during physical stress, and relieve pain when bound to the same receptors. In short, endorphins are the body’s natural opiates with a dual function—euphoria and pain relief.

The ventral tegmental area is the dopamine production area.

The nucleus accumbens is one of the brain’s main pleasure centers.

The prefrontal cortex is a site of working memory and planning.

The amygdala stores emotional memories.

The hippocampus is another memory center, that may actually produce some dopamine.

Heroin exploits the pleasure pathway

Heroin binds to the same endorphin receptors, but instead of doubling the amount of dopamine released in the pleasure pathway, it allows the release of about ten times the baseline concentration of dopamine. The result from this flood of dopamine is intense euphoria.

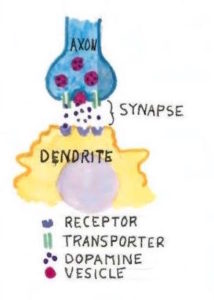

Although all drug addictions work through the dopamine pathway, the way the dopamine is handled differs for different drugs. Normally, the transporters (parallel green lines in the diagram) mop up the dopamine molecules from a synapse and transport them back to the cell that made them. Cocaine stops the transporter’s action, greatly increasing the amount of dopamine molecules in the synapse.

Although all drug addictions work through the dopamine pathway, the way the dopamine is handled differs for different drugs. Normally, the transporters (parallel green lines in the diagram) mop up the dopamine molecules from a synapse and transport them back to the cell that made them. Cocaine stops the transporter’s action, greatly increasing the amount of dopamine molecules in the synapse.

In the ventral tegmental area, surrounding inhibitory neurons control the release of dopamine. When opiates such as heroin bind to these surrounding neurons, the opiates overcome the inhibition and allow dopamine to flood the synapse.

In both cases, more dopamine will bind to the receptors.

The nervous system is not happy with huge fluctuations and tries to adjust—in technical terms, maintain homeostasis. With repeated exposure to heroin, the receptors become less effective. According to Dr. Jose Moron-Concepcion of Washington University, it is not clear whether the neurons actually produce fewer receptor molecules, or whether a change takes place in the downstream biochemistry.

As the receptors become less effective, more heroin is required to achieve the same effect—the ‘high’. This escalation is called tolerance.

The brain will become tolerant to all opioids—heroin, morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, etc.

Withdrawal

Heroin will attach to any neuron that has opioid receptors, not just the neurons controlling the pleasure pathway.

In the brainstem, which is the oldest part of the brain, heroin and other opioids inhibit the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (also called noradrenaline). This hormone regulates basic functions like wakefulness, breathing, blood pressure, smooth muscle tone, etc. Less norepinephrine means drowsiness, slowed respiration, lower blood pressure, constipation, etc.

The brain likes to adjust to normalcy—homeostasis again. Neurons make more norepinephrine in response to repeated opiate insults, trying to keep the body functioning well.

But when an opioid-tolerant brain suddenly does not get its drug, it can’t down-regulate norepinephrine production immediately. All that excess norepinephrine now causes jitters, muscle cramps, diarrhea and the other very unpleasant symptoms of withdrawal.

When a person takes an opiate to avoid withdrawal, that person is said to be dependent upon the drug.

Addiction—or ‘Gotta Have It’

About 17-22% of those who use opioids become addicted, meaning that the central motivation of their lives becomes getting the drug. The obsession interferes with work, with relationships, and often with rational concerns for safety.

Addiction involves the continuation and augmentation of that dopamine pathway. The neurons of the nucleus accumbens spread the happiness message to other areas of the brain. Memories of the good feelings are formed and stored in the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala . These memories may include the places where the drug was obtained, the apparatus used for injection if applicable, and perhaps other people involved if getting high was a social event.

Cravings for the drug, even in those who have been off the opioids for long periods can be irresistible in stress situations, or when triggers such as being in the company of addicted friends occur.

Because these cravings are so strong, addiction experts such as Waller emphasize that addiction must be treated as a chronic disease.

Complications of Prescription Opioids

The medical profession seems to be in complete agreement that morphine and its derivatives (opioids) are the most effective agents against acute pain. That is, if you break a leg or undergo surgery you will need these drugs for a time. When opioids and endorphins also bind to certain neurons in the midbrain, inhibitory pathways to the sensory part of the spinal column are activated—perhaps the origin of the expression ‘feeling no pain’.

When and if acute pain decreases, the inhibitory neural pathways are not needed as much. At some point, other pain relievers are sufficient for comfort. According to Waller, continuing use of opiods once pain decreases to a tolerable level can lead to tolerance, dependence, and perhaps addiction.

On the other hand, many times pain does not decrease or go away. A recent review by Moron and A. Wilson-Poe states that at any time about 40% of the population suffers from acute or chronic pain. Rodent models investigations by Moron and Dr. Ream Al-Hasani at St. Louis College of Pharmacy confirmed that chronic pain itself reduces the function of opiate receptors, and thus reduces the release of dopamine.

Lower dopamine levels can mean less happiness. But if opioids are the instrument for relieving pain, increasing levels of the drug will be needed for dopamine homeostasis. Many try to self-medicate with more pills, or the cheaper alternative, heroin. And there is an upper limit to how much opioid the body will tolerate before the dose becomes an overdose.

In an interview, Al-Hasani emphasizes that one of the responses to chronic pain can be ‘negative affect’ such as depression. Indeed, some portion of the perception of chronic pain may be the ‘negative affect’ itself. Some people with conditions causing chronic pain can be helped by anti-depressants or other treatments such as biofeedback.

Of course, there is an active search for non-opioid pain relievers more effective than ibuprofen or acetaminophen. According to the Wilson-Poe/Moron review, cannabinoids seem to show great promise in reducing the escalation of opiate doses in a synergistic manner.

Treating Addiction as a Chronic Disease

Most patients prescribed opiates for pain relief—even those who have developed a high tolerance for the drug and who take high doses—will gradually discontinue their use and their brain chemistry will return to normal.

Some people, however, progress to addiction. Scientists know that genetics plays a role in determining susceptibility to addiction, as well as addictions to other drugs such as alcohol. Younger brains, still developing, are more prone to develop the addiction syndrome.

Addiction causes changes in the brain that are semi-permanent at best, thanks to the intricacy of neural connections. Receptor levels may return to normal eventually, tolerance may disappear, but memories of highs, memories of pain or relief from unhappiness persist.

Medical treatment of heroin addiction is controversial because the available medicines are heroin analogs. Even though proper administration of these compounds allows the addict to resume a normal life, many argue that they just “substitute one addiction for another”.

However, most practitioners and researchers at this time agree that addiction is a chronic disease of the brain, and should be treated on a continuing basis as with any other chronic disease. It seems perfectly acceptable, for example, that diabetics will take insulin as often as needed to maintain the proper blood sugar levels.

Methadone

The synthetic heroin analog methadone has been around for a long time. Although very effective, it is available only at methadone treatment centers. The person wishing to wean away from heroin must report to the center daily to be tested and to receive the medication. Aside from the inconvenience of a daily appointment, at some clinics the patient is faced with temptation upon leaving the center because dealers congregate outside.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a semi-synthetic opioid that has great promise for treating addiction to heroin or drugs like oxycontin. In pharmacological jargon, it is called a partial agonist—meaning it binds to opioid receptors, but can’t cause the release of enough dopamine to cause a high. It is an excellent pain reliever. Because it is only a partial agonist, when it binds to the norepinephrine neurons of the brain stem, it does not inhibit norepinephrine release nearly as much as heroin or other strong opioids. Hence withdrawal symptoms are much reduced.

Buprenorphine is long-acting, meaning that it is slowly released from opioid receptors. When a routine and proper dosage is established, it can be taken as seldom as three times a week, and can be prescribed and monitored in a doctor’s office. It is usually prescribed as Suboxone, in combination with naloxone. If this tablet is dissolved under the tongue as directed, only the buprenorphine effects are seen. To prevent abuse, if the tablet is crushed and injected, naloxone takes over and withdrawal ensues.

Why is buprenorphine (Suboxone) therapy not more common?

Doctors must be specially licensed to prescribe buprenorphine, and must take special training to obtain the license. The drug itself is expensive—costs range from $200-$700 per month. Patients must be monitored, and usually require other support such as psychological counseling.

Hospital emergency departments see a great many overdose victims. Only about 15% of hospitals have physicians on staff who can prescribe buprenorphine. In the other 85%, the patient may be referred to a drug clinic, but is not given anything to begin addiction treatment while waiting as long as 3-4 weeks for an appointment at the clinic.

Washington University in Saint Louis Medical School, under the leadership of Dr. Evan Schwarz of the Emergency Medicine Department (ED)allows, has begun a program of buprenorphine bridging. He and fifteen other ED physicians are licensed to prescribe enough of the drug to those who request addiction treatment to make them feel fairly normal until they can get scheduled at a local addiction clinic. They are also paired with a counselor from a local program. This counselor will be a former addict.

Realists expect that most persons with an opioid addiction will relapse occasionally, but that if they are treated as patients rather than sinners, medical treatments such as buprenorphine will enable them to feel normal and lead normal lives.

For the Future…

A number of possible scenarios could alleviate the current opioid crisis, or aspects of it. Development of a potent non-opioid pain relief drug would be a boon for sufferers from chronic pain, and might allow faster weaning from opioids in the case of surgical or other events involving acute pain. A newly introduced indicator strip that allows heroin users to detect fentanyl contamination could help prevent overdoses. Training more physicians to prescribe bupenorphine may induce more patients with addiction to enter into treatment.

Continued research into brain function and chemistry is fundamental to development not only of better drugs, but of psychological and other strategies to deal with the crisis of addiction.

This is the second in a series of self-published articles. To get an email whenever there’s a new blog post, use the Subscribe form in the left sidebar.

Have a topic you’d like me to explore? Use the Contact Me link in the left sidebar.