One third of Missouri (15 million acres) is covered by forest. This forest is highly important to the state, both ecologically and economically, but is in danger from at least three exotic insect pests.

The European gypsy moth, the emerald ash borer, and the walnut twig beetle could wreak havoc on great numbers of trees. They seem to be headed our way. Actually, according to Perry Eckhardt, Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) urban forester, most experts expect that attack by these pests is inevitable. Fortunately, state and federal agencies have extensive programs in place to monitor appearances of these pests and to try to combat them if they establish footholds.

European Gypsy Moth

Even though they have yet to become established here, Missouri is like the bulls-eye on a target for European gypsy moths. According to Rob Lawrence, MDC’s entomologist, oak is their favorite of all the approximately 300 woody plants they eat. And Missouri has more forests with a higher percentage of oaks than any place in the United States.

Originally imported to Massachusetts in the late 1860’s as a possible commercial silkworm, the gypsy moth has spread over the entire northeast, and has now reached northeastern Illinois and Iowa.

Photo by Jon Yuschock, Bugwood.org | Forestryimages.org

It is the caterpillar that does the damage. Emerging from their egg masses in early spring and, responding to light, they climb to the top of the trees. During a two-month larval life, each caterpillar can eat about a square yard of leaves. Considering that one egg mass can hatch up to one thousand very hungry caterpillars, it is easy to see how trees can become defoliated. In 1981, gypsy moth larvae defoliated 12.9 million acres of forest, according to a U.S. Forest Service publication.

Interestingly, a very healthy hardwood tree can survive one or two complete defoliations, but will die with repeated assaults. However, some of our oak species, such as the red oaks that replaced pines logged in the early twentieth century are not especially hardy in this area and would succumb quickly.

The adult female of this species doesn’t even fly, but spends its adult life emitting sexual pheromones (airborne hormones) to attract males and thus fulfill its reproductive destiny.

Since the female can’t travel and eggs don’t move, how has the European gypsy moth spread across the northeastern United States?

Tree photo by J.S. Peterson @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database, leaf by Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org, gypsy moth by USDA APHIS PPQ Archive, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org | Forestryimages.org

First, the hair-covered larvae can ‘fly.’ On the high branches, they will spin a silk thread and dangle. Winds disperse them distances up to a mile. Then, on a new tree, they can feed, pupate, and emerge as an adult. If that adult is a female, and lays eggs on the tree, a new site of infestation is born.

Second, females lay eggs on any surface, including undersides of trucks and campers. The highways can then bring egg masses to new locations.

Because the potential for destruction is so high, six agencies in the state—including the army and national guard–cooperate to monitor for any new infestation. Each year, they hang 6000-10,000 triangular orange cardboard boxes baited with the gypsy moth sex attractant pheromone. The males can’t resist it. (Note: Gardeners who have trapped Japanese beetles with sex pheromone traps will recognize the power of those airborne molecules)

The monitors greatly increase the density of traps in any location where a gypsy moth male has been discovered. So far, so good—the moth has not taken a foothold in Missouri. If a population does seem to be established in the future, however, the invasive pest control experts know what to do.

The pheromone is commercially available, and can be formulated into tiny flakes or creams that can be spread around the forest. The males will become overstimulated and disoriented and not able to find a real female moth. This technique, called mating disruption, works best when populations are building.

Eventually, gypsy moth population explosions slow down because of factors like a fungus that kills them. But during the explosion phase, they can do great harm.

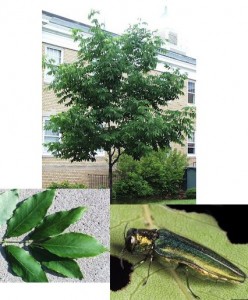

Emerald Ash Borer

Oaks will survive the gypsy moth, but a new insect arrival from Asia has the potential to destroy an entire genus, the ash trees, in America. Since the first emerald ash borer in the U.S. was identified in 2002, it has caused the destruction of literally millions of green, white, and black ash trees. It apparently came in some packing crates shipped to the Great Lakes area, and has been spreading rapidly from there.

Wayne County, Missouri, near Lake Wappapello has already been attacked, and the insect has been identified 75 miles from St. Louis in Salem, Illinois.

The 1/2 inch long beetle with big eyes lays its eggs in the crevices of ash tree bark. When the larvae hatch they burrow under the bark and eat the underlying tubes that carry water and nutrients up and down the tree. Eventually the tree starves to death.

This beetle can fly ½ mile to a new tree, but forest entomologists think a major reason for its spread is on firewood transported from site to site. People will cut up dead trees for wood, and the wood is sold to campers or homeowners with fireplaces.

Forests have great importance to the Missouri economy, says Jason Jensen of MDC. Leaving aside recreational value, forest products make big contributions to the annual economy.

- Over $9 billion in revenues from products ranging from hardwoods for furniture to pallets

- About 32,000 jobs–logging, sawmills, wood treatment plants

- $57 million in state sales taxes

Missouri leads in these products:

- White oak barrels for aging whiskey and wine

- Charcoal, made from residues produced in sawmills

- Black walnut meats

Ash comprises only 3% of Missouri’s forests, but because of its beauty has been used extensively in urban plantings. The Misouri average for urban plantings is 14% ash, but many neighborhoods 30-40% and some as much as 80%.

According to Tom Bradley of the National Park Service, the Arch grounds have 1000 ash trees—50% of its tree population. The Park Service is investigating 8-10 other hardy trees for a replacement if the ash borer makes it necessary.

Loss of urban trees has a major effect on property values, removal and replacement costs, as well as the environmental impact on carbon dioxide uptake and shade effects on heating and cooling.

Tree and leaf photos by Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org. Emerald ash borer photo by David Cappaert, Michigan State University, Bugwood.org | Forestryimages.org

According to Daniel Weinbach, Chicago landscape architect, the ash borer has already destroyed thousands of trees in that area. Since most of the local governments have now outlawed the planting of ash, nurseries have had to destroy their stock and ash wood products cannot be sold to other states.

The tools for dealing with this recently arrived pest are not nearly as well developed as those for gypsy moths. No sex pheromone is commercially availabe, so the purple “Barney traps” used to track the spread of the emerald ash borer are baited with oil that imitates the odors of stressed ash trees. Food is apparently not as strong an attractant as sex, so the traps are correspondingly less sensitive.

Without the elegant solution of mating disruption, methods to limit infestations usually involve destroying the tree. Foresters will sometimes deliberately create clusters of stressed trees by removing a foot-wide ring of bark. Since the ash borer prefers to attack trees that are already stressed, many eggs will be laid in these magnet trees—which are then burned over the winter to kill their insect residents. And of course imposed quarantines are the other primary tool to slow down the spread.

Experiments with tiny wasps parasitic on the green beetles have begun in other states, including Illinois.

Thousand Cankers disease

Thousand Cankers disease, discovered in 2008, is converging on Missouri from both east and west. It has the potential to eradicate an entire species, the black walnut tree. The black walnut is economically important for both its nutmeat, and its timber used for fine woodworking. In fact, a recent study projected about $850 million lost in Missouri over 20 years if the black walnut were to disappear – read more.

As with Dutch elm disease, the real killer is a fungus that lives on the body surface of a beetle, the walnut twig beetle. When this tiny beetle tunnels under the bark to lay its eggs, some of the fungus rubs off and begins to form sores called cankers. The larvae feed on the tree’s interior, pupate there, and when the new adults emerge they are covered with fungus.

Tree and leaf photo by Robert Vidéki, Doronicum Kft., Bugwood.org. Walnut twig beetle photo by Steven Valley, Oregon Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org | Forestryimages.org

Tiny is the operative word, according to Collin Wamsley, chief entomologist of the Missouri Department of Agriculture. The insect is the size of the “i” in the word “liberty” on a dime. Tens of thousands can infest a tree, and each will create a canker. Because the beetles and the lesions they create are so small, it takes several years for the symptoms to occur.

The disease seems to have started in the far southwest, where the native Arizona walnuts tolerate the insect and its fungus. Black walnut trees, however, which are not native to the Southwest are quite susceptible.

Somehow, the insect has been carried to three eastern states where the black walnut is native, probably along with lumber to be used in woodworking.

Because thousand cankers is such a new threat, sophisticated monitors and treatments are just being developed. At present, says Simeon Wright of MDC, they are conducting visual surveys at high-risk locations such as campsites and near lumber mills. They look for black walnut trees with wilting leaves, excessive dieback in the upper canopy, and lots of vigorous shoots lower down that the trees send out trying to compensate for upper canopy loss.

But next year they hope to have some pheromone traps for better monitoring. This particular pheromone signals insects of the species to aggregate, so it should attract on-the-move insects to the traps for early detection.

What you can do: Buy locally, burn locally

Conservation and agriculture agencies across the country are trying to get out a simple message: When it comes to firewood, buy locally and burn locally. Never buy firewood from more than 50 miles away, never transport it more than 50 miles, and burn all you have. Firewood from diseased trees is thought to be the main culprit in letting these insect pests hitchhike to new locations.

This article was originally published in the St. Louis Beacon.